Today is December 11, but back in 1899, the Battle of Magersfontein occurred during the Anglo-Boer War. This was the battle where the Scandinavian Free Corps proved their quality.

A chapter from my Book Orania Building a Nation

Get your copy on Amazon:

THE DALESMEN OF AFRICA

For those interested in South Africa, or who have Afrikaner friends, Bok van Blerk’s song ’De la Rey’ is hard to avoid. Inspired by the history of the Boer War, the song resonates strongly with today’s Afrikaners. It serves as a modern myth depicting a people under pressure and in need of leadership, while evoking the image of the legendary Boer General De la Rey. The song has become a unifying force that clarifies the group and what is expected of them. It arouses feelings of belonging and identity and emphasizes the existential value of defending one’s culture and land.

This song was followed by another, almost equally iconic, song from the same artist, ”Afrikanerhart,” which also deals with the Second Boer War. This song addresses the Battle of Magersfontein as a symbol of Afrikaner resistance and resilience. Both songs evoke a collective sense of applied history, struggle, and survival, urging unity and resistance against an external enemy.

For those who are Scandinavian or have an interest in military history, a visit to Magersfontein is almost obligatory when in Orania. Just 50 miles north of Orania, as the crow flies, lies this battlefield that holds special significance for both Boers and Scandinavians. It was here that the Scandinavian Corps fought side by side with the Boers during the initial stages of the Second Boer War, specifically on December 11, 1899.

Many Scandinavians were already in South Africa, working in sectors such as shipping, mining, and railways. These Northerners had a positive view of the Boers and considered it a moral duty to support their quest for self-rule and resistance against British imperialism. When the war broke out, a volunteer corps was organized under the leadership of railway engineer Christer Uggla. This corps became part of the Transvaal army and consisted of 114 men, nearly half of whom were Swedes. The rest were Norwegians, Danes, and Finns. The corps was trained as mounted infantry, and the officers were democratically elected by the troops themselves, in accordance with Boer practice.

The corps was led by Johannes Flygare, a missionary’s son raised in South Africa, who was elected as captain. The lieutenants were Erik Stålberg and William Bärentzen, of whom only Stålberg had a military background as a sergeant in the Swedish army. An ambulance unit was also attached to the corps, led by the Norwegian doctor Wilhelm Bidenkap and supported by three Swedish nurses.

Under General Piet Cronje’s command, the volunteer corps was tasked with defending the town of Kimberley. They positioned themselves on ridges in the otherwise flat terrain around Magersfontein. The battle there became a trial for the corps. While the Boer soldiers were protected in their trenches, the Scandinavians were placed as an advance guard, approximately 1,500 meters in front of the main line. Unable to dig trenches in the rocky soil, they had to face the enemy’s assault in the chilly and dark night.

At four in the morning, the British began their assault on the main position, and soon the Scandinavians in the outpost were also drawn into the intense fighting. The attack was repelled, and General Cronje ordered a withdrawal of the outposts. Unfortunately, this order never reached the Scandinavians.

At dawn, a new British attack followed. Despite heavy losses, they managed to encircle the Scandinavian corps. It was a hundred Scandinavians who had successfully held out for several hours, pitted against a superior force of 3,500 soldiers from the Scottish Highland Brigade. The Boers ultimately won the Battle of Magersfontein, partly thanks to the delaying action fought by the Scandinavians.

The fallen were buried on the battlefield, and several monuments were erected to honor their memory. One of these monuments, placed at the site where the corps had been entrenched, bears an inscription in Swedish: ”De kunde icke vika, blott falla kunde de” (”They could not yield; they could only fall”). On the ridge next to this monument stands a large runestone, surrounded by four smaller stones, each adorned with a Valkyrie. These Valkyries bear names representing the Nordic countries: Svea for Sweden, Nora for Norway, Dana for Denmark, and Suomi for Finland. On the Valkyries’ shields, the names of the fallen Scandinavians are engraved.

After the successful Battle of Magersfontein, Boer General Cronjé reported: ”Next to God, the (Boer) republics have the Scandinavian corps to thank for the victory.” The corps’ brave efforts gave rise to a nationalist hero status in the Nordic countries, where it was generally believed that they had fought for a righteous cause.

Nils Svedenborg, originally from Borås, Sweden, but working at the post office in Johannesburg during the Boer War, reported back to Sweden: ”In Transvaal, the Swedes have an exceptionally good reputation. After the Scandinavian corps’ tragic but heroic end in the bloody battle at Magersfontein, several Boer leaders have stated that ’with 10,000 such lads, we would soon have taken the whole of the Cape Colony.’”

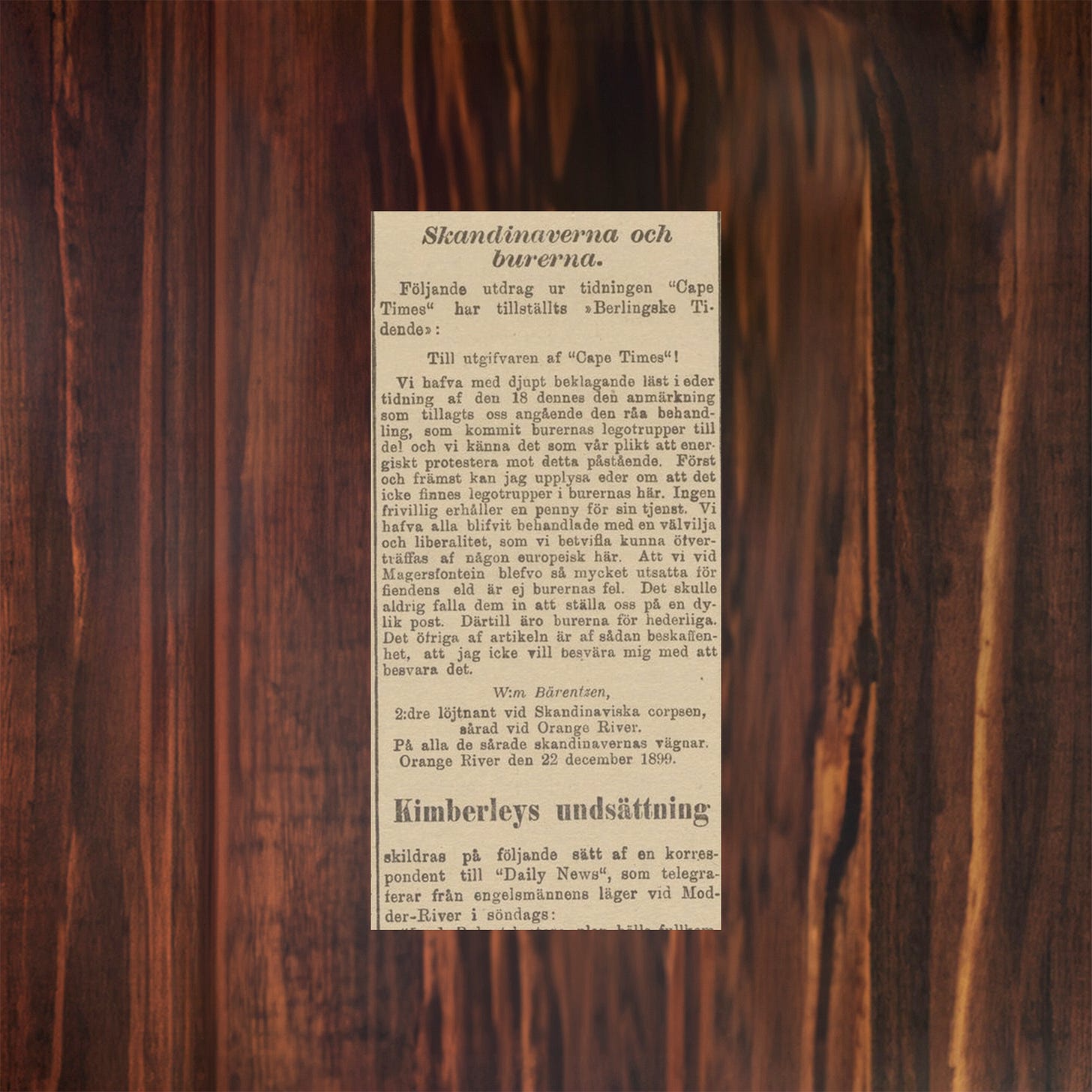

In Göteborgs Aftonblad on February 24, 1900, a response was published from Second Lieutenant William Bärentzen, who served in the Scandinavian Corps and was wounded at Magersfontein. The response was a reaction to an article in the British-controlled newspaper Cape Times, which had described foreign volunteers in the Boer army as mercenaries and claimed that they were poorly treated by the Boers. Bärentzen clarified on his own behalf and on behalf of all other wounded Scandinavians: There are no mercenary troops in the Boer army. No volunteer receives a penny for their service. We have all been treated with a goodwill and liberality that we doubt can be surpassed by any European army. That we were so exposed to enemy fire at Magersfontein is not the fault of the Boers. They would never place us in such a position. They are too honorable for that.

Signed: William Bärentzen, Second Lieutenant in the Scandinavian Corps, wounded at Orange River. On behalf of all wounded Scandinavians. Orange River, December 22, 1899.

Magersfontein is located near the Orange River, hence the mention. In Afrikaans, the river is called ’Oranjerivier,’ and it is this river that has given rise to the name Orania.

The broad Nordic support for the Boers during the Boer War was a complex phenomenon that united both right-wing and left-wing forces. This solidarity can be seen as a natural consequence of a desire to support the weaker party being attacked by an imperialist superpower, in this case, Great Britain. However, it was not merely a David versus Goliath issue.

This solidarity aligned with the prevailing ideas in the Nordic countries at the time. On one hand, there was a national-romantic and bourgeois current, influenced by German culture and politics, that supported the Boers. On the other hand, there were liberal and socialist movements, which were particularly skeptical of British imperialism.

In summary, the support for the Boers reflected a range of different political and cultural currents. This multifaceted solidarity was not limited to Sweden but existed throughout the Nordic region.

In the Swedish press at the time of the Boer War, the Boers were described as ’Afrikas dalakarlar’ (’The Dalesmen of Africa’).

In the Swedish cultural context, being compared to a ”Dalesmen” from Dalarna is a significant compliment. The people of Dalarna are often seen as embodying the quintessential Swedish virtues of resilience, independence, and a close connection to the land. By likening the Boers to the Dalesmen of Africa, the Swedish press was attributing to them qualities of steadfastness, cultural integrity, and a strong sense of identity. It was a way to express admiration for their resilience and self-reliance, traits highly valued in both cultures.

Göteborgs Aftonblad wrote in 1901 something that could have been written today about the Boers in South Africa: ”The Boers are a friendly, good-natured people, who did not want to harm anyone, and who wished for nothing more than to live in peace and quiet, under the protection of their own culture and untouched by the political conflicts around the world.”

It is fascinating that a Swedish media description over a hundred years old can still resonate so true in a contemporary South African enclave like Orania. This enclave can be seen as a modern manifestation of the Boer culture that was once so warmly portrayed in the Swedish press.

If you enjoyed this chapter, don't forget to pick up your own copy of the book.

Best regards

Jonas Nilsson