Among Boers and Britons: Heroic Raids and Daring Escapes

The Scandinavian Free Corps’ Bold Defiance in the South African War

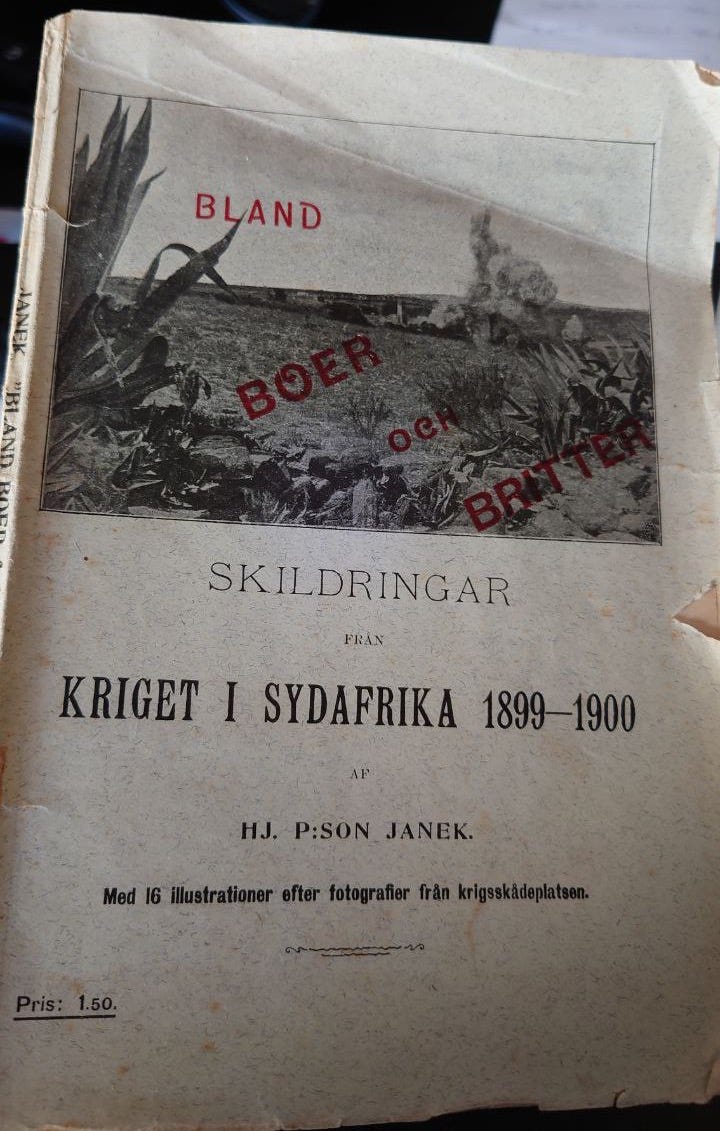

I’ve just finished reading Among Boers and Britons: Tales from the War in South Africa 1899-1900 by Swedish volunteer Hjalmar Pettersson Janek. The book recounts his experiences during the early phase of the Second Boer War, highlighting raids, escapes, and the realities of warfare in South Africa. Janek’s story offers insight into both the courage of the Scandinavian Free Corps and the changing nature of the conflict.

📘 Order Among Boer and Britons on Amazon

In 1901, as the Second Boer War still raged across South Africa, a remarkable book was published. Written by Swedish volunteer Hjalmar Pettersson Janek, "Among Boers and Britons: Tales from the War in South Africa 1899-1900" provides a glimpse into a time when warfare, despite its brutality, still maintained elements of honor and chivalry that seem almost incomprehensible today. Janek's account captures the war's earlier phase, before it devolved into what would become one of history's darkest chapters. When conventional military tactics failed to break Boer resistance, the British would later resort to a scorched earth policy and the establishment of concentration camps where thousands of Boer women and children would perish from disease and malnutrition. This systematic targeting of civilians marked a turning point not just in this conflict, but in the nature of modern warfare itself. But Janek's narrative comes from an earlier moment, when the opposing sides still operated under more traditional codes of military honor.

Janek was one of roughly 100 Scandinavians who formed the Scandinavian Free Corps, fighting alongside the Boers against the British Empire. Their story, particularly at the Battle of Magersfontein, would earn them immortal recognition - not just from their Boer allies, but even from their British opponents.

The Corps' valor at Magersfontein, where they held an advanced position against overwhelming odds, facing the elite Scottish Highland Brigade, earned them a memorial that stands to this day. The inscription, written in Swedish, reads "De kunde icke vika, blott falla kunde de" ("They could not yield; they could only fall"). Five rune stones mark the site - one large central stone encircled by four smaller ones, each bearing a Valkyrie representing the Nordic nations: Svea for Sweden, Nora for Norway, Dana for Denmark, and Suomi for Finland.

But it's Janek's personal story that truly captures the spirit of that era. After being captured at Magersfontein, he would make several daring escapes from British captivity. During one attempt, he allowed himself to be buried in sand on a beach, breathing through a hollow seaweed stalk while his comrades carefully covered him. He remained there for two hours until the guards had departed, feeling soldiers walking directly over his buried form.

As I lay down in a hollow, several of the Scandinavians covered me with sand. I could now breathe only through a hollow seaweed which I held in my mouth as a breathing tube. I had to lie there for 2 hours, until all the others had returned to the camp. I could hear the trumpet signal that announced the end of bathing time (rarely has any music sounded sweeter to a pair of ears) and could feel how the soldiers marched over my legs.

Fortunately, the soldiers had enough sense not to step on my eyes. It was, however, very painful to lift the mass of sand with my chest for each breath, but manageable it was, though I felt I could not have endured much longer.

Stiff and thirsty, I crawled out of the sand hole and under the fence. Luckily, the sentry was looking in another direction and before he turned around, I had crawled under and seated myself on the other side, casually throwing pebbles into the sea. It should be noted that it was not unusual for large groups of curious onlookers to gather outside the fence, which made it easy for the guard to believe I was one of them. Then I crept along the rocks past all the guard posts.

I now went up to the English camp, which lay to the right of the prisoners'. From Fägersköld I had received a decent suit and from a Dutch officer a collar and some other small luxuries along with 2 pounds in money. What the soldiers thought of my person, I do not know; presumably they took me for a civilian-dressed officer; they all saluted and I nodded back.

I now marched down to the beach again and watched how the soldiers bathed. Gradually I came to the final obstacle, the fence that encloses the soldiers' camp. There stood two English officers critically observing a horse. They were, however, too far away to see on which side of the fence I was. When they turned around, I jumped over, and when they looked in my direction again, I walked slowly away, a comparatively free man.

After having met several English officers, among others the duty officer Captain Trydell-Perkins, with whom I was personally acquainted, and avoided being recognized and discovered by them by pulling down my hat and looking the other way, I came to the railway station and bought a return ticket to Wynburg. There I bought another ticket to Cape Town and went aboard a ship destined for the east coast.

The relationship between captors and captives reflects a lost code of honor. When Janek finally succeeded in escaping to Portuguese East Africa (modern Mozambique), he sent a postcard to the British camp commander: "In grateful memory of the brief but pleasant time I had the pleasure of being your guest." Rather than taking offense, the commander subsequently forwarded all mail addressed to Janek at the prison camp to his new address in Mozambique, unopened.

This kind of civility extended even to planned escape attempts. One where they tried to dig themselves out with their tunnel-digging operation, which moved 17 tons of sand over two months, was met with relative understanding when discovered. The British response focused more on preventing future attempts than punishment.The Scandinavians had even prepared humorous "property listings" to post on the camp bulletin board after their escape:

FOR SALE!

Due to owner's sudden departure for Pretoria, Villa 'Empty Manger' is hereby offered for sale. Interested parties should contact Captain Perkins, who, enjoying our complete confidence, has full authority to manage this matter as he sees fit.

The Scandinavian volunteers earned tremendous respect from the Boers, who credited them with the victory at Magersfontein. As Boer General Cronjé reported: "Next to God, the republics have the Scandinavian corps to thank for the victory."

Prior to the battle of Magersfontein while the Boers were positioned north of Scholtznek awaiting the British advance, the Scandinavian Corps found ways to both entertain themselves and harass the enemy. Their favorite "sport," as Janek describes it in his memoir, involved stealing horses and mules from British lines - an activity that required both stealth and what he calls "a touch of impudence."

The British cavalry would leave their horses and mules to graze during the hottest hours of the day, typically under the watch of African guards who carried no weapons. The Scandinavians quickly discovered this vulnerability. Though they couldn't conduct large-scale raids without drawing the full attention of the British camp, small groups of men familiar with the terrain could successfully capture animals. Each successful raid brought not only personal satisfaction from outwitting the enemy but also financial rewards - captured war materiel was split 50-50 between the captors and the Boer government.

These raids from the Scandinavians caught the attention of General Cronje, who was impressed by theirs ability to disrupt British infrastructure and supply lines. As a reward, he presented them with what Janek describes as a "fine gift" - a beautifully painted cart pulled by six excellent mules and loaded with dynamite, fuses, spades, and picks. This gift enabled more ambitious operations deep behind enemy lines, including the demolition of railway culverts some 20 kilometers from Modder River. As Janek delightedly reports, there was never a shortage of volunteers for these dangerous missions - "the supply of willing workers always exceeded demand when it came to something exciting."

The exploits of these Scandinavian raiders before Magersfontein show a different side of the war than major battles. For these volunteers, warfare included what Janek simply calls 'sport' - the thrilling game of outsmarting a numerically superior enemy through cunning and daring. These small-unit actions and guerrilla tactics would later become a signature of Boer resistance, but for now, they were almost treated as an adventure game. Reading his account, one gets the sense that these operations were as much about excitement as military necessity. The way he describes their raids, with obvious enthusiasm and good humor, shows how these men viewed their wartime experiences - almost as if it were simply their chosen way of life.

This spirit of adventure would carry Janek far beyond the African continent. After the war, he would eventually make his way to Mexico, where he met his end in 1928, shot to death under circumstances that remain unclear. But his account of the Boer War preserves a unique window into a time when warfare, while no less deadly, still operated under codes of honor that seem almost foreign to modern sensibilities.

Today, the monuments at Magersfontein stand as more than just memorials to battlefield courage. They represent a shared heritage of European presence and nation-building in Africa - a legacy that continues to resonate. The battle for sovereignty and self-determination that brought Scandinavian volunteers to fight alongside Boers remains relevant today, though in different forms, both for Scandinavians and Boers alike.

For those interested in how this history lives on in contemporary Afrikaner culture, I recommend listening to Bok van Blerk's powerful song 'Afrikanerhart', which commemorates the Battle of Magersfontein.

Until next time

Jonas Nilsson

PS: Now republished: 📘 Order Among Boer and Britons on Amazon